This article is the first in a series of articles that discuss the architecture, development, and deployment of a C/C++ cross-platform plugin framework. This first installment explores the terrain, surveys (briefly) several existing plugin/component libraries, delves into the binary compatibility problem, and presents some desirable properties of the solution.

Subsequent articles showcase an industrial strength plugin framework that you can use on Windows, Linux, Mac OS X, and easily port to other operating systems. The plugin framework has some unique properties compared to other alternatives and it is designed to be flexible, efficient, easy for application developers, easy for plugin writers, supports both C and C++, and provides multiple deployment options (as dynamic or static libraries).

I will develop as a sample application a simple role-playing game that lets you add non-player characters (NPCs) plugins. The game engine loads the plugins and seamlessly integrates their contents. The game demonstrates the concepts and shows concrete running code.

Plugins are the way to go if you want to develop a successful and dynamic system. Plugin-based extensibility is the current best practice to extend and evolve systems in a safe manner. Plugins let third-party developers add value to systems and let in-house developers add functionality without risk of destabilizing the core functionality. Plugins promote separation of concerns, guaranty implementation details hiding, isolated testing, and many other best practices.

Platforms like Eclipse are actually bare-bones frameworks where all the functionality is provided by plugins. The Eclipse IDE itself (including the UI and the Java Development Environment) is just a set of plugins hooked into the core framework.

C++ is notoriously non-accommodating when it comes to plugins. C++ is extremely platform-specific and compiler-specific. The C++ standard doesn't specify an Application Binary Interface (ABI), which means that C++ libraries from different compilers or even different versions of the same compiler are incompatible. Add to that the fact that C++ has no concept of dynamic loading and each platform provide its own solution (incompatible with others) and you get the picture. There are a few heavyweight solutions that try to address more than just plugins and rely on some additional runtime support. Still, C/C++ is often the only practical option when it comes to high-performance systems.

Before embarking on a brand new framework, it's worth checking out existing libraries or frameworks. I found that there are either heavyweight solutions like Microsoft's COM and Mozilla's XPCOM (Cross-platform COM), or pretty basic offerings like Qt's plugins and a few articles about creating C++ plugins. One interesting library is DynObj that claims to solve the binary compatibility problem (with some restrictions). There is also a proposal for adding plugins to C++ as a native concept by Daveed Vandervoorde. It's an interesting read, but it feels strange.

None of the basic solutions address the myriad issues associated with creating an industrial strength plugin-based system like error handling, data types, versioning, separation between framework code, and application code. Before diving into the solution, let's understand the problem.

Again, there is no standard C++ ABI. Different compilers (and even different versions of the same compiler) produce different object files and libraries. The most obvious manifestation of this problem is the different name mangling algorithms implemented by different compilers. This means that in general you can only link C++ object files and libraries that were compiled using exactly the same compiler (brand and version). Many compilers don't even implement standard C++ features from the C++98

There are some partial solutions to this problem. For example, if you access a C++ object only through a virtual pointer and call only its virtual methods you sidestep the name mangling issue. However, it is not guaranteed that even the virtual table layout in memory is identical between compilers, although it is more stable.

If you try to load C++ code dynamically you face another issue -- there is no direct way to load and instantiate C++ classes from a dynamic library under Linux or Mac OS X (Visual C++ supports it under Windows).

The solution to this issue is to use a function with C linkage (not name mangled by the compiler) as a factory function that returns an opaque handle to the caller. The caller then casts the handle to the appropriate class (usually a pure abstract base class). This requires some coordination, of course, and works only if the library and the application were compiled with compilers that have a matching vtable layout in memory.

The ultimate in compatibility is to just forget about C++ and expose a pure C API. C is compatible in practice between all compiler implementations. Later I'll show how to achieve C++ programming model on top of C compatibility.

A plugin-based system can be divided into three parts:

The domain-specific system loads the plugins and creates plugin objects via the plugin manager. Once a plugin object is created and the main system has some pointer/reference to it, it can be used just like any other object. Usually, there are some special destruction/cleanup requirements as we shall see.

The plugin manager is a pretty generic piece of code. It manages the life-cycle of the plugins and exposes them to the main system. It can find and load plugins, initialize them, register factory functions and be able to unload plugins. It should also let the main system iterate over loaded plugins or registered plugin objects.

The plugins themselves should conform to the plugin manager protocol and provide objects that conform to the main system expectations.

In practice, you rarely see such a clean separation (in C++-based plugin systems, anyway). The plugin manager is often tightly coupled with the domain-specific system. There is a good reason for that. Plugin managers need to provide eventually instances of plugin objects with certain type. Moreover, the initialization of the plugin often requires passing domain-specific information and/or callback functions/services. This can't be done easily with a generic plugin manager.

Plugins are usually deployed as dynamic libraries. Dynamic libraries allow many of the advantages of plugins such as hot swapping (reloading a new implementation without shutting the system), safe extension by third-party developers (additional functionality without modifying the core system), and shorter link times. However, there are situations where static libraries are the best vehicle for plugins. For example, some systems simply don't support dynamic libraries (many embedded systems). In other cases, security concerns don't allow loading foreign code. Sometimes, the core system comes with pre-loaded with some plugins and it is more robust to statically link them to the main executable (so the users can't delete them by accident).

The bottom line is that a good plugin system should support both dynamic and static plugins. This lets you deploy the same plugin-based system in different environments with different constraints.

Plugins are all about interfaces. The basic notion of plugin-based system is that there is some central system that loads plugins it knows nothing about and communicates with them through well-defined interfaces and protocols.

The naive approach is to define a set of functions as the interface that the plugin exports (either dynamic or static library). This approach is technically possible but conceptually it is flawed. The reason is that there are two kinds of interfaces a plugin should support and can be only a single set of functions exported from a plugin. This means that both kinds of interface will be mixed together.

The first interface (and protocol) is the generic plugin interface. It lets the central system initialize the plugin, and lets the plugin register with the central system various functions for creating and destroying objects as well as global cleanup function. The generic plugin interface is not domain-specific and can be specified and implemented as a reusable library. The second interface is the functional interface implemented by the plugin objects. This interface is domain-specific and must be carefully designed and implemented by the actual plugins. The central system should be aware of this interface and interact with the plugin objects through it.

Listing One is the header file that specifies the generic plugin interface. Without delving into the details and explaining anything just yet let's just see what it offers.

#ifndef PF_PLUGIN_H #define PF_PLUGIN_H#include <apr-1/apr_general.h>

#ifdef __cplusplus extern "C" { #endif

typedef enum PF_ProgrammingLanguage { PF_ProgrammingLanguage_C, PF_ProgrammingLanguage_CPP } PF_ProgrammingLanguage; struct PF_PlatformServices_;

typedef struct PF_ObjectParams { const apr_byte_t * objectType; const struct PF_PlatformServices_ * platformServices; } PF_ObjectParams;

typedef struct PF_PluginAPI_Version { apr_int32_t major; apr_int32_t minor; } PF_PluginAPI_Version;

typedef void * (*PF_CreateFunc)(PF_ObjectParams *); typedef apr_int32_t (*PF_DestroyFunc)(void *);

typedef struct PF_RegisterParams { PF_PluginAPI_Version version; PF_CreateFunc createFunc; PF_DestroyFunc destroyFunc; PF_ProgrammingLanguage programmingLanguage; } PF_RegisterParams;

typedef apr_int32_t (*PF_RegisterFunc)(const apr_byte_t * nodeType, const PF_RegisterParams * params); typedef apr_int32_t (*PF_InvokeServiceFunc)(const apr_byte_t * serviceName, void * serviceParams);

typedef struct PF_PlatformServices { PF_PluginAPI_Version version; PF_RegisterFunc registerObject; PF_InvokeServiceFunc invokeService; } PF_PlatformServices;

typedef apr_int32_t (*PF_ExitFunc)();

typedef PF_ExitFunc (*PF_InitFunc)(const PF_PlatformServices *);

#ifndef PLUGIN_API #ifdef WIN32 #define PLUGIN_API __declspec(dllimport) #else #define PLUGIN_API #endif #endif

extern #ifdef __cplusplus "C" #endif PLUGIN_API PF_ExitFunc PF_initPlugin(const PF_PlatformServices * params); #ifdef __cplusplus } #endif #endif /* PF_PLUGIN_H */

The first thing you should notice is that it is a C file. This allows the plugin framework to be compiled and used by pure C systems and to write pure C plugins. But, it is not limited to C and is actually designed to be used mostly from C++.

The PF_ProgrammingLanguage enum allows plugins to declare to the plugin manager if they are implemented in C or C++.

The PF_ObjectParams is an abstract struct that is passed to created plugin objects.

The PF_PluginAPI_Version is used to negotiate versioning and make sure that the plugin manager loads only plugins with compatible version.

The functions pointer definitions PF_CreateFunc and PF_DestroyFunc (implemented by the plugin) allow the plugin manager to create and destroy plugin objects (each plugin registers such functions with the plugin manager)

The PF_RegisterParams struct contains all the information that a plugin must provide to the plugin manager upon initialization (version, create/destroy functions, and programming language).

The PF_RegisterFunc (implemented by the plugin manager) allows each plugin to register a PF_RegisterParams struct for each object type it supports. Note that this scheme allows a plugin to register different versions of an object and multiple object types.

The PF_InvokeService function pointer definition is a generic function that plugins can use to invoke services of the main system like logging, event notification and error reporting. The signature includes the service name and an opaque pointer to a parameters struct. The plugins should know about available services and how to invoke them (or you can implement service discovery if you wish using PF_InvokeService).

The PF_PlatformServices struct aggregates all the services I just mentioned that the platform provides to plugin (version, registering objects and the invoke service function). This struct is passed to each plugin at initialization time.

The PF_ExitFunc is the definition of the plugin exit function pointer (implemented by the plugin).

The PF_InitFunc is the definition of the plugin initialization function pointer.

The PF_initPlugin is the actual signature of the plugin initialization function of dynamic plugins (plugins deployed in dynamically linked libraries/shared libraries). It is exported by name from dynamic plugins, so the plugin manager will be able to call it when loading the plugin. It accepts a pointer to a PF_PlatformServices struct, so all the services are immediately available upon initialization (this is the right time to register objects) and it returns a pointer to an exit function.

Note that static plugins (plugins implemented in static libraries and linked directly to the main executable) should implement an init function with C linkage too, but MUST NOT name it PF_initPlugin. The reason is that if there are multiple static plugins, they will all have a function with the same name and your compiler will hate it.

Static plugins initialization is different. They must be initialized explicitly by the main executable that will call their initialization function with the PF_InitFunc signature. This is unfortunate because it means the main executable needs to be modified whenever a new static plugin is added/removed and also the names of the various init functions must be coordinated.

There is a technique called "auto-registration" that attempts to solve the problem. Auto-registration is accomplished by a global object in the static library. This object is supposed to be constructed before the main() even starts. This global object can request the plugin manager to initialize the static plugin (passing the plugin's init() function pointer). Unfortunately, this scheme doesn't work in Visual C++.

What does it mean to write a plugin? The plugin framework is very generic and doesn't provide any tangible objects your application can interact with. You must build your application object model on top of the plugin framework. This means that your application (that loads the plugins) and the plugins themselves will have to agree about and coordinate their interaction model. Usually it means that the application expect the plugin to provide certain types of objects that expose some specific API. The plugin framework will provide all the infrastructure necessary to register, enumerate and load those objects. Example 1 is a definition of a C++ interface called IActor. It has two operations -- getInitialInfo() and play(). Note that this interface is not sufficient because getInitialInfo() expects a pointer to a struct called ActorInfo and play() expects a pointer to yet another interface called ITurn. This is usually the case and you must design and specify a whole object model.

struct IActor

{

virtual ~IActor() {}

virtual void getInitialInfo(ActorInfo * info) = 0;

virtual void play( ITurn * turnInfo) = 0;

};

Each plugin can register multiple types that implement the IActor interface. When the application decides to instantiate an object registered by a plugin, it invokes the registered PF_CreateFunc implemented by the plugin. The plugin is responsible to create a corresponding object and return it to the application. The return type is void * because the object creation operation is part of the generic plugin framework that knows nothing about the specific IActor interface. The application then casts the void * to the an IActor * and can work with it through the interface as if it was a regular object. When the application is done with the IActor object it invokes the registered PF_DestroyFunc implemented by the plugin and the plugin destroys the actor object. Pay no attention to the virtual destructor behind the curtain. I'll discuss it in the next installment.

In the binary compatibility section I explained that you can have C++ vtable-level compatibility if you use compilers with matching vtable layouts for the application and the plugins or you can use C-level compatibility and then you can use different compilers to build the application and the plugins, but you are limited to C interaction. Your application object model must be C-based. you can't use a nice C++ interface like

In pure C programming model you simply develop your plugin in C. When you implement the PF_CreateFunc function you return a C object that interacts with further C object in your application C object model. What is all this talk about C objects and C object models. Everybody knows C is a procedural language and has no concept of objects. This is correct and still C has enough abstraction mechanism to implement objects including polymorphism (which is necessary in this case) and support object-oriented programming style. In fact, the original C++ compiler was actually a front-end to a C compiler. It produced C code from the C++ code that was later compiled using a plain C compiler. It's name Cfront is more than telling.

The ticket is to use structs that contain function pointers. The signature of each function should accept its own struct as first argument. The struct may also contain other data members. This simple idiom corresponds to a C++ class and provides encapsulation (state and behavior in one place), inheritance (by using the first data member for a base struct), and polymorphism (by setting different function pointers).

C doesn't support destructors, function, and operators overloading and namespaces so you have fewer options when defining interfaces. That may be a blessing in disguise because interfaces are supposed to be used by other people who may master a different subset of the C++ language. Reducing the scope of language construct in interfaces may improve the simplicity and usability of your interfaces.

I will explore object-oriented C in the context of the plugin framework in the follow up articles. Listing Two contains the C object model of the sample game that accompanies this article series (just to whet your appetite). If you take a quick look you can see that it even supports a form of collections and iterators beyond plain objects.

#ifndef C_OBJECT_MODEL #define C_OBJECT_MODEL#include <apr-1/apr.h>

#define MAX_STR 64 /* max string length of string fields */

typedef struct C_ActorInfo_ { apr_uint32_t id; apr_byte_t name[MAX_STR]; apr_uint32_t location_x; apr_uint32_t location_y; apr_uint32_t health; apr_uint32_t attack; apr_uint32_t defense; apr_uint32_t damage; apr_uint32_t movement; } C_ActorInfo;

typedef struct C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle_ { char c; } * C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle; typedef struct C_ActorInfoIterator_ { void (*reset)(C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle handle); C_ActorInfo * (*next)(C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle handle);

C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle handle; } C_ActorInfoIterator;

typedef struct C_TurnHandle_ { char c; } * C_TurnHandle; typedef struct C_Turn_ { C_ActorInfo * (*getSelfInfo)(C_TurnHandle handle); C_ActorInfoIterator * (*getFriends)(C_TurnHandle handle); C_ActorInfoIterator * (*getFoes)(C_TurnHandle handle);

void (*move)(C_TurnHandle handle, apr_uint32_t x, apr_uint32_t y); void (*attack)(C_TurnHandle handle, apr_uint32_t id);

C_TurnHandle handle; } C_Turn;

typedef struct C_ActorHandle_ { char c; } * C_ActorHandle; typedef struct C_Actor_ { void (*getInitialInfo)(C_ActorHandle handle, C_ActorInfo * info); void (*play)(C_ActorHandle handle, C_Turn * turn);

C_ActorHandle handle; } C_Actor; #endif

In pure C++ programming model you simply develop your plugin in C++. The plugin programming interface functions can be implemented as static member functions or as plain static/global functions (C++ is mostly a superset of C after all). The object model can be your garden variety C++ object model. Listing Three contains the C++ object model of the sample game. It is almost identical to the C object model of Listing Two.

#ifndef OBJECT_MODEL #define OBJECT_MODEL#include "c_object_model.h"

typedef C_ActorInfo ActorInfo;

struct IActorInfoIterator { virtual void reset() = 0; virtual ActorInfo * next() = 0; };

struct ITurn { virtual ActorInfo * getSelfInfo() = 0; virtual IActorInfoIterator * getFriends() = 0; virtual IActorInfoIterator * getFoes() = 0;

virtual void move(apr_uint32_t x, apr_uint32_t y) = 0; virtual void attack(apr_uint32_t id) = 0; };

struct IActor { virtual ~IActor() {} virtual void getInitialInfo(ActorInfo * info) = 0; virtual void play( ITurn * turnInfo) = 0; }; #endif

In the dual C/C++ programming model you can develop your plugin in either C or C++. When you register your objects you specify if they are C or C++ object. This is useful if you create a platform and you want to provide third-party developers ultimate freedom to choose their programming language and programming model and mix and match C and C++ plugins.

The plugin framework supports it, but the real work is in devising a dual C/C++ object model to your application. Each object type needs to implement both C interface and the C++ interface. This means that you will have a C++ class with a standard vtable and also a bunch of function pointers that correspond to the methods of the virtual table. The mechanics are not trivial and I'll demonstrate it in the context of the sample game.

Note that from the point of view of a plugin developer the dual C/C++ model doesn't introduce any additional complexity. The plugin developer always develop either a C or a C++ plugin using C interfaces or the C++ interfaces.

In hybrid C/C++ programming models, you develop your plugin in C++ but under the covers the C object model is used. This involves creating C++ wrapper classes that implement the C++ object model and wrap corresponding C objects. The plugin developers programs against this layer that translates every call, parameter and return value back and forth between C and C++. This requires additional work when implementing your application object model, but is very straight forward usually. The benefit is a nice C++ programming model for the plugin developer with a full C-level compatibility. I don't demonstrate it in the context of the sample game.

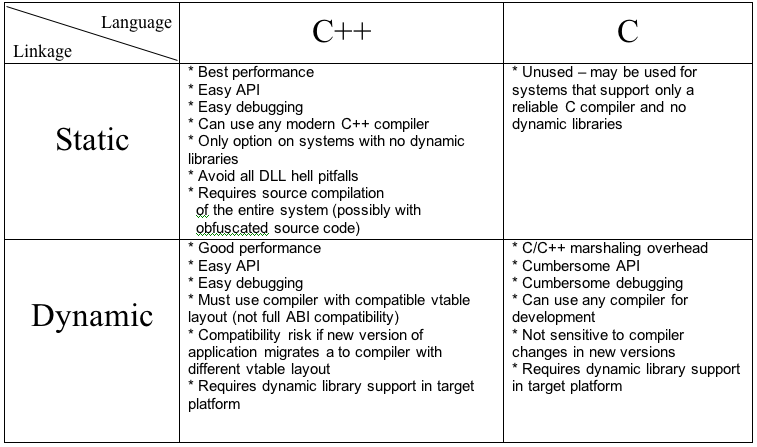

Figure 1 shows the various pros and cons of different combinations of deployment models (static vs. dynamic libraries) and programming language choice (C vs. C++).

For the sake of this discussion the dual C/C++ model has the prerequisites and limitations of C++ if using C++ plugins and the prerequisites and limitations of C if using C plugins. Also, the hybrid C/C++ model is just a C model because the C++ layer is hidden behind the plugin implementation. This can all be confusing, but the bottom line is that you have options and the plugin framework allows you to make choices and pick the tradeoffs you feel appropriate to your situation. It doesn't force you to use a specific model and it doesn't aim to lowest common denominator.

This article is the second in a series of articles about developing cross-platform plugins in C++. The first article described the problem in detail, explored various solutions, and introduced the plugin framework. In this installment, I describe the architecture and design of a plugin-based system based on the plugin framework, the lifecycle of a plugin, and the internals of the generic plugin framework. Beware! Some code may surface here and there.

A plugin-based system can be divided into three parts that are loosely coupled: The main system or application with its object model, the plugin manager and the plugins themselves. The plugins conform to the plugin manager's interfaces and protocols and also implement the object model interfaces. Let's illustrate it with a concrete example. The main system is a turn-based game. The game takes place in a battlefield that contains various monsters. The hero fights the monsters until he dies or all the monsters die. Pretty basic yet gratifying. Listing One is the definition of the Hero class.

#ifndef HERO_H #define HERO_H#include <vector> #include <map> #include <boost/shared_ptr.hpp> #include "object_model/object_model.h" class Hero : public IActor { public: Hero(); ~Hero(); // IActor methods virtual void getInitialInfo(ActorInfo * info); virtual void play(ITurn * turnInfo); private: }; #endif

The BattleManager is the engine that drives the game. It takes care of instantiating the hero and the monsters and populating the battlefield. Then in each turn it calls upon each actor (hero or monsters) to do their worst via the play() method.

The hero and the monsters implement the IActor interface. The hero is a built-in game object with a predefined behavior. The monsters on the other hand are implemented as plugin objects. This allows the game to be extended with new monsters and decouples the development of new monsters from the development of the main game engine. The PluginManager's job is to abstract away the fact that monsters are spawned from plugins and present them to the BattleManager as actors just like the hero. This scheme also allows the game to come with some built-in monsters that are statically linked in and are not implemented in plugins. The BattleManager shouldn't even be aware ideally there is such a thing as plugins. It should just operate at the C++ object level. This makes it easier to test too, because you can create mock monster in the test code without having to write a full-fledged plugin.

The PluginManager itself can be either generic or specialized. A generic plugin manager is unaware of the specific underlying object model. When a C++ PluginManager instantiates a new object implemented in a plugin it must return a generic interface, which the caller must cast to the actual interface from the object model. This is a little ugly, but necessary. A custom PluginManager is aware of your object model and can operate in terms of the underlying object model. For example, a custom PluginManager for our game can have a CreateMonster() function that returns an IActor interface. The PluginManager I show is a generic one, but I'll demonstrate how simple it is to put an object model specific layer on top of it. This is standard practice because you don't want your application code to deal with explicit casts.

It's time to figure out the lifecycle of the plugin system. The application, PluginManager and the plugins themselves participate in a complicated dance according to a strict protocol. The good news are that the generic plugin framework can mostly orchestrate the process. The application gets access to the plugins when it needs it and the plugins just need to implement a few functions that will be called in due time.

Static plugins are plugins that are deployed in static libraries and are linked statically into the application. The registration can be done automatically if the library defines a global registrar object whose constructor is called automatically. Unfortunately it doesn't work on all platforms (e.g., Windows). The alternative is to explicitly tell the PluginManager to initialize static plugin by passing it a dedicated init function. Since, all the static plugin are statically linked to the main executable the init() function (which must have the signature of PF_InitPlugin) of each plugin must have a unique name. A good convention is something like <Plugin Name>_InitPlugin(). Here is the prototype of the init() function of a static plugin called "StaticPlugin":

extern "C" PF_ExitFunc StaticPlugin_InitPlugin(const PF_PlatformServices * params)

The explicit initialization creates a tight coupling between the main application and the static plugins because the main application need to "know" at compile time what plugins are linked to it in order to initialize them. The process can be automated as part of the build if all the static plugins follow some convention that the build process can use to find them and generate the code that initializes each one of them on-the-fly.

Once a static plugin's init() function is called it will register all its object types with the PluginManager.

Dynamic plugins are the more common ones. They should all be deployed in a dedicated directory. The application should invoke the PluginManager's loadAll() method and pass the dedicated directory path. The PluginManager scans all the files in this directory and load every dynamic library. The application may alternatively call the load() method, which loads a single plugin if it wants fine-grained control about what plugins are loaded exactly.

Once a dynamic library has been loaded successfully, the PluginManager is looking for a well-known function entry point called PF_initPlugin. If such an entry point is found, the PluginManager initializes the plugin by calling this function and passing the PF_PlatformServices struct. This struct contains the PF_PluginAPI_Version, which lets the plugin perform some version negotiation and decide if it can function properly. If the application's version is inappropriate the plugin may decide to fail the initialization.The PluginManager logs the fact that the plugin wasn't initialized properly and continues to load the next plugin. It is not a fatal error from the point of view of the PluginManager if a plugin fails to load or initialize. The application may perform additional checks by enumerating the loaded plugins and verify that no crucial plugin is missing.

Listing Two contains the PF_initPlugin function of the C++ plugin (and its exit function).

#include "cpp_plugin.h"

#include "plugin_framework/plugin.h"

#include "KillerBunny.h"

#include "StationarySatan.h"

extern "C" PLUGIN_API apr_int32_t ExitFunc()

{

return 0;

}

extern "C" PLUGIN_API PF_ExitFunc PF_initPlugin(const PF_PlatformServices * params)

{

int res = 0;

PF_RegisterParams rp;

rp.version.major = 1;

rp.version.minor = 0;

rp.programmingLanguage = PF_ProgrammingLanguage_CPP;

// Regiater KillerBunny

rp.createFunc = KillerBunny::create;

rp.destroyFunc = KillerBunny::destroy;

res = params->registerObject((const apr_byte_t *)"KillerBunny", &rp);

if (res < 0)

return NULL;

// Regiater StationarySatan

rp.createFunc = StationarySatan::create;

rp.destroyFunc = StationarySatan::destroy;

res = params->registerObject((const apr_byte_t *)"StationarySatan", &rp);

if (res < 0)

return NULL;

return ExitFunc;

}

The ball is now in the hands of the plugin itself (inside the PF_initPlugin code). If the version negotiation went well, the plugin should register all the object types it supports with the plugin manager. The purpose of the registration is to provide to the application functions like PF_CreateFunc and PF_DestroyFunc that it can use later on to create and destroy plugin objects. This arrangements allows the plugin to control the actual creation and destruction of objects including any resources they manage (like memory), but lets the application control the number of objects and their lifetime. Of course, a plugin may implement singletons by always returning the same object instance.

The registration is done by preparing for each object type registration record (PF_RegisterParams) and calling the registerObject() function pointer provided in the PF_PlatformServices struct (that was passed as argument to PF_initPlugin). The registerOBject() function accepts a string that uniquely identifies the object type or a wildcard "*" and the PF_RegisterParams struct. I'll explain the purpose of the type string and how it is used in the next section. The reason a type string is necessary is because different plugins may support multiple types of objects.

You can see in Listing Two that the C++ plugin registers two monster types -- "KillerBunny" and "StationarySatan".

Now, the shoe is on the other foot. Once the plugin calls registerObject() control goes back to the PluginManager. The PF_RegisterParams contains also a version and a programming language fields. The version field lets the PluginManager make sure it can work with this object type. If there is a version mismatch it will not register the object. It is not a fatal error. This allows fairly flexible negotiations, where the plugin tries to register multiple versions of the same object type in order to take advantage of newer interfaces if they exist and fallback to older interfaces. The programming language field will be explained soon. If the plugin manager is happy with the PF_RegisterParams struct, it just stores it in an internal data structure that maps the object type to the PF_RegisterParams struct.

After the plugin registered all its object types, it returns a function pointer to a PF_ExitFunc. This function is called before the plugin is unloaded and lets the plugin clean up any global resources it acquired during its life time.

If the plugin decides that it can't function properly (can't allocate some resource, crucial object type registration failed, version mismatch) it should cleanup after itself and return NULL. This signals the PluginManager that the plugin initialization failed. The PluginManager will also remove all registrations performed by the failed plugin.

At this point all the dynamic plugins have been loaded and both static and dynamic plugins have been initialized and registered all the object types they support. The application can now create object instances by calling the PluginManager's createObject() method. This method accepts an object type string and an IObjectAdapter interface. I'll discuss object adaptation in the next section, so let's focus on the object type string. The application needs to know what object types are supported. This knowledge can be hard-coded into the application or it can query the plugin's manager registration map and find out at runtime what object types are currently registered.

If you recall, the type string can be either a unique type identifier or a wildcard "*". When the application calls createBbject() with a type string ("*" is an invalid type string) the PluginManager looks for an exact match in its registration map. If it find a match it will invoked the registered PF_CreateFunc and return the result to the application (possibly after adaptation). If it can't find a match it will go over all the wild card registrations (plugins that registered with "*" type string) and let them try by invoking their registered PF_CreateFunc. If any plugin returns a non-NULL result it is returned to the application.

What is the purpose of the wildcard registration? It lets plugins create objects they don't know about at registration time. What? Yes. In Numenta, we used it to allow Python plugins. A single C++ plugin registered with a "*" type string. If the application requested a Python class (the type was the actual qualified import path of a Python class) then the C++ plugin who had an embedded Python interpreter created a special object that held an instance of the Python class and forwarded plugin requests to its internal Python object (via the Python C API). To the application it appeared as a standard C++ object. This allows great flexibility because it is possible to just drop a Python class in the right place even while the system is running and the Python object is immediately available.

Again, the plugin framework supports both C and C++ plugins. C and C++ plugin objects implement different interfaces. The main innovation I present in the next installment is how to design and implement a dual C/C++ object model. That unified object model can be transparently accessed and manipulated by both C and C++ objects. However, if the application had to deal with each plugin using its native interface, it would be highly inconvenient. The application code would be peppered with if statements and every argument would have to be converted to the proper data type, which is also very inefficient. The plugin framework uses two techniques to overcome these obstacles.

The actual adaptation is done using an object adapter. This is an object provided by the application (just a specialization of the ObjectAdapter template provided by the plugin framework) that implements the IObjectAdapter interface.

Listing Three contains the IObjectAdapter interface and the ObjectAdapter template.

#ifndef OBJECT_ADAPTER_H #define OBJECT_ADAPTER_H#include "plugin_framework/plugin.h" // This interface is used to adapt C plugin objects to C++ plugin objects. // It must be passed to the PluginManager::createObject() function. struct IObjectAdapter { virtual ~IObjectAdapter() {} virtual void * adapt(void * object, PF_DestroyFunc df) = 0; }; // This template should be used if the object model implements the // dual C/C++ object design pattern. Otherwise you need to provide // your own object adapter class that implements IObjectAdapter template<typename T, typename U> struct ObjectAdapter : public IObjectAdapter { virtual void * adapt(void * object, PF_DestroyFunc df) { return new T((U *)object, df); } }; #endif // OBJECT_ADAPTER_H

The PluginManager uses it to adapt a C object to a C++ object. I explain the process in detail when I go over the various components of generic plugin framework later in this article.

The important thing to take home is that the plugin framework provides all the necessary infrastructure necessary to adapt a C object to a C++ object, but it needs the application's help because it doesn't know the types of objects it needs to adapt.

The application simply calls C++ member functions on the C++ interfaces of plugin objects (possibly adapted C objects) it created. In addition to dutifully returning results from their member functions, the plugin objects may also invoke callback functions through the PF_InvokeService function of the PF_PlatformServices struct. These services can be used for diverse purposes like logging, error reporting, progress notifications of long running operations, and event propagation. Again, these callbacks are part of the protocol between the application and plugins and must be designed as part of the entire application interfaces and object model design.

The best practice in managing object lifetime is that the creator is also the destroyer. This is especially important in a language like C++ where you are responsible for memory allocation and deallocation. There are many ways to allocate and deallocate memory: malloc/free, new/delete, array new/delete, OS specific APIs that allocate/deallocate from different heaps, etc. It is often very important to deallocate using the deallocation method that corresponds to the allocation method. The creator is in the best position to know how resources where allocated. In the plugin framework every object type is registered with both a create function and a destroy function (PF_CreateFunc and PF_DestroyFunc). Plugin objects are created using PF_CreateFunc and should be destroyed using PF_DestroyFunc. Each plugin is responsible for implementing both properly so all resources are cleaned up properly. The plugin is free to implement any memory scheme it wants. All the plugin objects may be allocated statically and PF_DestroyFunc may do nothing or there could be a pool of pre-created instances and PF_DestroyFunc may just return an object to the pool. The application just creates objects using PF_CreateFunc and releases them when its done with them using PF_DestroyFunc. The destructor of C++ plugin objects does the right thing, so the application doesn't have to deal with calling PF_DestroyFunc directly and can dispose of plugin objects using the standard delete operator. This works for adapted C objects too, because the object adapter makes sure to call the proper PF_DestroyFunc in its destructor.

When the application exits it needs destroy all the plugin objects it created and notify all the plugins (both static and dynamic) that it's time to cleanup. The application does it by calling the PluginManager's shutdown()PluginManager in turn calls the PF_ExitFunc of each plugin (returned from the PF_initPlugin function if successful) and unloads all the dynamic plugins. It is important to call the exit function even if the application is about to exit and all the memory the plugins hold will be reclaimed automatically. The reason is that there are other types of resources that are not reclaimed automatically and also because the plugins might have some buffered state they need to commit/flush/send over the network etc. Lucky for the application the PluginManager takes care of that.

In some situations the application may also choose to unload only a single plugin. In this case too, the exit function must be called, the plugin itself unloaded (if it's a dynamic plugin) and removed from all the PluginManager's internal data structures.

This section describes the main components of the generic plugin framework and what they do. You can find all these components in the plugin_framework subdirectory of the source code.

The DynamicLibrary component is a simple cross-platform C++ class. It uses the dlopen/dlclose/dlsym system calls on UNIX (including the Mac OS, X) and the LoadLibrary/FreeLibrary/GetProcAddress API calls for Windows.

Listing Four is the header file for DynamicLibrary.

#ifndef DYNAMIC_LIBRARY_H #define DYNAMIC_LIBRARY_H#include <string> class DynamicLibrary { public: static DynamicLibrary * load(const std::string & path, std::string &errorString); ~DynamicLibrary(); void * getSymbol(const std::string & name); private: DynamicLibrary(); DynamicLibrary(void * handle); DynamicLibrary(const DynamicLibrary &); private: void * handle_; }; #endif

Each dynamic library is represented by an instance of the DynamicLibrary class. Loading a dynamic library involves calling the static load() method that returns a DynamicLibrary pointer if everything was fine or NULL if it failed. The errorString output argument contains the error message if any. The dynamic library will store the platform-specific handle used to represent the loaded library, so it will be available for getting symbols and unloading later.

The getSymbol() method is used to get symbols out of loaded library and the destructor unloads the library (just delete the pointer).

There are different ways to load dynamic libraries. For simplicity, DynamicLibrary just picks one option on each platform. It is possible to extend it, but due to platform differences the interface will not be simple anymore.

PluginManager is the big Kahuna of the plugin framework. Everything that has to do with plugins goes through the PluginManager. Listing Five contains the header file the PluginManager.

#ifndef PLUGIN_MANAGER_H #define PLUGIN_MANAGER_H#include <vector> #include <map> #include <apr-1/apr.h> #include <boost/shared_ptr.hpp> #include "plugin_framework/plugin.h"

class DynamicLibrary; struct IObjectAdapter;

class PluginManager { typedef std::map<std::string, boost::shared_ptr<DynamicLibrary> > DynamicLibraryMap; typedef std::vector<PF_ExitFunc> ExitFuncVec; typedef std::vector<PF_RegisterParams> RegistrationVec; public: typedef std::map<std::string, PF_RegisterParams> RegistrationMap; static PluginManager & getInstance(); static apr_int32_t initializePlugin(PF_InitFunc initFunc); apr_int32_t loadAll(const std::string & pluginDirectory, PF_InvokeServiceFunc func = NULL); apr_int32_t loadByPath(const std::string & path); void * createObject(const std::string & objectType, IObjectAdapter & adapter); apr_int32_t shutdown(); static apr_int32_t registerObject(const apr_byte_t * nodeType, const PF_RegisterParams * params); const RegistrationMap & getRegistrationMap(); private: ~PluginManager(); PluginManager(); PluginManager(const PluginManager &); DynamicLibrary * loadLibrary(const std::string & path, std::string & errorString); private: bool inInitializePlugin_; PF_PlatformServices platformServices_; DynamicLibraryMap dynamicLibraryMap_; ExitFuncVec exitFuncVec_;

RegistrationMap tempExactMatchMap_; // register exact-match object types RegistrationVec tempWildCardVec_; // wild card ('*') object types RegistrationMap exactMatchMap_; // register exact-match object types RegistrationVec wildCardVec_; // wild card ('*') object types }; #endif

The application initiates the loading of plugins by calling PluginManager::loadAll(), passing the directory that contains the plugins. The PluginManager loads all the dynamic plugins and initializes them. It stores every dynamic plugin library in the dynamicLibraryMap_, every exit function in exitFuncVec_ (for both dynamic and static plugins) and every registered type in the exactMatchMap_. Wildcard registrations are stored in the wildCardVec_. The PluginManager is now ready to create plugin objects. If there are static plugins they are registered too (either by the application or via auto-registration).

During plugin initialization the PluginManager keeps all registrations in temporary data structures that are merged into exactMatchMap_ and wildCardVec_ if the initialization is successful and discarded if it fails. This transactional behavior guaranties that all stored registrations come from successfully initialized plugins that are still loaded into memory.

When the application needs to create a new plugin object (either dynamic or static) it calls the PluginManager::createObject() and passes an object type and an adaptor. The PluginManager creates the object using the registered PF_CreateFunc and adapts it from C to C++ if it's a C object (based on the PF_ProgrammingLanguage member of the registration struct).

At this point, the PluginManager gets out of the picture. The application interacts with the plugin object directly and finally destroys it. The PluginManager is blissfully ignorant of all these interactions. It is the responsibility of the application to destroy plugin objects before the plugin is unloaded (or at least not call its methods after its plugin was unloaded).

The PluginManager is in charge of unloading the plugins too. The PluginManager::shutdown() method should be called the application after it destroyed all the plugin objects it created. The shutdown() calls the exit function of all the plugins (both static and dynamic), unloads all the dynamic plugins and clears all the internal data structures. It is possible to "restart" the PluginManager by calling its loadAll() method. The application may also "restart" static plugins by calling the PluginManager::initializePlugin() for each one. Static plugins that used auto-registration will be gone for good.

If the application forgets to call shutdown(), the PluginManager will call it in its destructor.

The ObjectAdapter's job is to adapt a C plugin object to a C++ plugin object as part of object creation. The IObjectAdapter interface is straightforward. It defines a single method (besides the mandatory virtual destructor) -- adapt. The adapt() method accepts a void pointer, which will be a C object and PF_DestroyFunc function pointer that can destroy the C object. It is supposed to return a C++ object that wraps the C object. It is the responsibility of the application to provide a proper wrapper object. The plugin framework can't do it because this task requires knowledge of the application object model. However, the plugin framework provides the ObjectAdapter template that simply performs a static_cast of the C object to the wrapper object provided by the application (see Listing Three).

The resulting object can be passed to any context that requires the C++ interface. This will be the main focus of the next article in this series, so don't sweat it if it sounds a little obscure at the moment. The main point here is that the ObjectAdapter template provides an implementation of the IObjectAdapter interface that the application can specialize to its own C plugin object and its C++ wrapper.

Listing Six contains the ActorFactory that subclasses a specialization of the ObjectAdapter template. It functions as an adapter from a C object that implements the C_Actor to the ActorAdapter C++ object that implements the IActor interface. ActorFactory also provides a static createActor() function that calls the PluginManager's createObject() with itself as the adapter and casts the resulting void pointer to an IActor pointer. This lets the application call a friendly createActor() static function with just an actor type and not mess with adapters and casts.

#ifndef ACTOR_FACTORY_H #define ACTOR_FACTORY_H#include "plugin_framework/PluginManager.h" #include "plugin_framework/ObjectAdapter.h" #include "object_model/ActorAdapter.h"

struct ActorFactory : public ObjectAdapter<ActorAdapter, C_Actor> { static ActorFactory & getInstance() { static ActorFactory instance; return instance; } static IActor * createActor(const std::string & objectType) { void * actor = PluginManager::getInstance().createObject(objectType, getInstance()); return (IActor *)actor; } }; #endif // ACTOR_FACTORY_H

The PluginRegistrar lets static plugins register their objects automatically with the PluginManager without requiring the application to explicitly initialize them. The way it works (when it works) is that the plugin defines a global instance of the PluginRegistrar and passes it its initialization function (with a signature that matches PF_InitFunc). The PluginRegistrar simply calls the PluginManager::initializePlugin() method that ignites the static plugin initialization just like with dynamic plugins after loading the dynamic library; see Listing Seven.

#ifndef PLUGIN_REGISTRAR_H

#define PLUGIN_REGISTRAR_H

#include "plugin_framework/PluginManager.h"

struct PluginRegistrar

{

PluginRegistrar(PF_InitFunc initFunc)

{

PluginManager::initializePlugin(initFunc);

}

};

#endif // PLUGIN_REGISTRAR_H

That's it for now. In the next installment, I examine the issues that involved in cross-platform development and the dual C/C++ object model, among other topics.

This is the third article in a series of articles entitled "Building Your Own Plugin Framework" that is about developing cross-platform plugins in C++. The first article described the problem in detail, explored various solutions and introduced the plugin framework. The second article explored the architecture and design of a plugin-based systems based on the plugin framework, the lifecycle of a plugin and the internals of the generic plugin framework. This article covers cross-platform development, miscellaneous topics like platform services provided to plugins by the system, error handling, and design and implementation of a dual C/C++ object model.

Cross-platform development in C/C++ is hard. Really hard. There are data type differences, compiler differences and OS API differences. The key to cross-platform development is to encapsulate platform differences so your main application code can concentrate on your application's logic. If your application code is bogged down in platform-specific code and has lots of #ifdef OS_THIS and #ifdef OS_THAT, it's a sure sign you need some refactoring. A good practice is to completely isolate all platform-specific code into a separate library or set of libraries. The ideal is that if you need to support a totally new platform you will need to modify only the code of the platform support library.

The first order of business when targeting multiple platforms is to understand and be aware of the differences. If you target 32-bit and 64-bit platforms, you need to understand the ramifications. If you target Windows, you need to be aware of ANSI/MBCS versus Unicode/Wide string. If you target a mobile device with a stripped down OS, you need to know what subset is available for you.

The next order of business is to pick a good cross-platform library. There are several good libraries. Most of them focus on UI. I chose to use the Apache Portable Runtime (APR) for the plugin framework. APR is the foundation of the Apache web server, the subversion server and a few other projects.

But APR might not be right for you. It is fully documented, but the documentation is not stellar. There isn't a big thriving community. There are no books and relatively a small number of projects use it. To top it off it's a C library and you might not like the naming conventions. However, it is very portable and robust (at least the parts used by Apache and Subversion) and you know it can be used to implement high-performance systems.

Consider writing a custom wrapper to your cross-platform library (just the parts you use). There are several benefits to this approach:

There are also a disadvantages:

I chose to write a wrapper for APR because it is a C library that require that you release resources explicitly, deal with memory pools for efficient memory allocation and I didn't like the naming conventions and the entire feel. I also used a relatively small subset (just directory and file APIs), but it was still a significant work to do it, test it and debug it. You can see the Path and Directory classes in the plugin_framework subdirectory. Note, that I use the APR typedefs for basic types as is without wrapping them in my own typedefs. This is just out of laziness and not a recommended practice. You can see the APR types all over the place in structs and interfaces.

The integral types C++ inherited from C are a cross-platform hazard. int, long and friends have different sizes on different platforms (32-bit and 64-bit on today's systems, maybe 128-bit later). For some applications it might seem irrelevant because they never approach the 32-bit limit (or rather 31-bit if you use unsigned integers), but if you serialize your objects on a 64-bit system and deserialize on a 32-bit system you might be unpleasantly surprised. Again, no easy breaks here. You need to understand the issues and do the right thing, which is make sure the sending/saving side and the receiving/loading side agree on the number of bytes of each value. File format or network protocol designers must be smart about it.

APR provides a set of typedefs for basic types that might be different on different platforms. These typedefs provide a guaranteed size and avoid the fuzzy built-in types. However, for some applications (mostly numerical) it is sometimes important to use the native machine word size (typically what int stands for) to achieve maximal performance.

Sometimes you must write larger chunks of platform-specific code. For example, APR's support for dynamic libraries wasn't adequate for the plugin framework needs. I simply implemented the DynamicLibrary class, which is a cross-platform abstraction of the dynamic library concept with a neutral interface. It is not always possible to do it without losing expressiveness or performance. You need to make your own trade-offs and expose to the application what you must. In the case of DynamicLibrary I preferred a minimal interface that doesn't allow the application to specify any flags to dlopen() on Unix and I used the simpler LoadLibrary() on Windows in lieu of the more flexible LoadLibraryEx().

Today, it's common practice to reuse third-party code. There are many good libraries with liberal licenses. Your project is likely to use a few of them too. In cross-platform environment it is important to select the third-party libraries you use wisely. In addition to standard selection criteria like robustness, performance, ease of use, documentation and support, you need to pay attention to the way the library is developed and maintained. Some libraries have not been developed in a cross-platform fashion from the beginning. It is common to see libraries that are used mostly on one platform and ported as an afterthought to other platforms. If the code base is not unified, it is a red flag. If there is a small number of users on a particular platform it is a red flag. If the core developers or maintainers don't don't package the library for all platforms it is a red flag. If when new version comes out, some platforms lag behind it is a red flag. A red flag doesn't mean you shouldn't use the library. It just means that all other things being equal you should prefer a library without red flags.

A good automated build system is crucial for the development of non-trivial software systems. If you throw in several flavors of your system (Standard, Pro, Enterprise), a couple of platforms (Windows, Linux, Mac OS X) and a few build variants (Debug, Release) you get an exponential explosion of artifacts. The build system must be fully automated and support the full build lifecycle -- get the source code from the source control system, do any pre-processing, compile, link, run unit tests and integration tests, package and distribute, possibly run full system tests, and report the results to all the stakeholders.

I'm a little fanatic about build systems and automation, but you won't be sorry for investing in your build system.

Platform services are services provided to the plugins by your system or application. I call them "platform services" because the generic plugin framework can service as a platform for plugin-based systems. The PF_PlatformServices struct contains the version, the registerObject function pointer and the invokeService function pointer; see Example 1.

typedef apr_int32_t (*PF_RegisterFunc)(const apr_byte_t * nodeType, const PF_RegisterParams * params);

typedef apr_int32_t (*PF_InvokeServiceFunc)(const apr_byte_t * serviceName, void * serviceParams);

typedef struct PF_PlatformServices

{

PF_PluginAPI_Version version;

PF_RegisterFunc registerObject;

PF_InvokeServiceFunc invokeService;

} PF_PlatformServices;

The version lets the plugin know the version of PluginManager it is hosted in. It lets the plugin make version-specific decisions like register different types of objects depending on the version of the host.

The registerObject() function is a PluginManager service through which the plugin registers its objects (without it there will be no plugin system).

The invokeService function is for application-specific services. The normal interaction between the application and the plugins (once the plugin objects have been created) is that the application invokes plugin object methods through the object model interfaces (e.g., IActor::play()). But, it is often desirable for a plugin to request some service from the application. It happens a lot when the application provides some managed execution environment where objects log progress, report errors or allocate memory in a centralized way. The application typically provides a standard logger, error reporting function, and memory allocator and all the objects use them. These service objects are often singletons or static functions and methods. Dynamic plugins can't access them directly. Unlike the registerObject service, the application-specific can't be defined in the generic PF_PlatformServices struct, because they are not known and to the generic plugin framework and they will be different for different applications. The application may wrap all these service access points and define a big struct that contains all of them and pass it to each plugin object through an object model interface method (e.g., initObject()) that every plugin object must implement. This is not always convenient in the presence of C plugins. The service objects are most likely implemented in C++ and accept and return C++ objects as arguments, maybe they are templated and maybe they throw exceptions. It is possible to provide a C compatible wrapper for each one. However, often it is easier to funnel all the service requests through a single sink that handles all the interaction with the plugins.

This is what invokeService() is all about. The signature is very simple -- a string for the service name and a void pointer to arbitrary struct. This is a weakly typed interface, but it provides absolute flexibility. The plugin and the application must coordinate the available services and what the params struct should be. Example 2 demonstrates a logging service that accepts a filename, line number, and message and logs.

LogServiceParams.h

==================

typedef struct LogServiceParams

{

const apr_byte_t * filename;

apr_uint32_t line;

const apr_byte_t * message;

} LogServiceParams;

Some Application File...

========================

#include "LogServiceParams.h"

apr_int32_t InvokeService(const apr_byte_t * serviceName,

void * serviceParams)

{

if (::strcmp(serviceName, "log") == 0)

{

LogServiceParams * lsp = (LogServiceParams *)serviceParams;

Logger::log(lsp->filename, lsp->line, lsp->message);

}

}

The LogServiceParams struct is defined in a header file that both the plugin and the application #include. This provides the logging protocol between them. The plugin packs the current filename, line number and log message in the structs and calls the invokeService() function with "log" as the service name and a pointer to the struct (as a void *). The implementation of the invokeService() function on the application side gets the pointer to the struct as a void pointer casts it to LogServiceParams struct and then calls the Logger::log() method with the information. If the plugin doesn't send a proper LogServiceParams struct the behavior is undefined (but definitely bad). The invokeService() can be used to handle multiple service requests and can let the plugin know by returning -1 that it failed. If the application needs to return a result to the plugin, output variable can be added to the service params struct. Each service may have its own params struct.

For example if the application wants to control memory allocation because it uses a custom memory allocation scheme it can provide an "allocate" and "deallocate" service. Whenever the plugin needs to allocate memory instead of doing malloc or new on its own it will call the "allocate" service and the AllocateServiceParams struct will contain the requested size and an output void * (or char *) for the allocated buffer.

Error handling is a little different with C++ plugin-based systems. You can't just throw exceptions in your plugin and expect them to be handled by the application. This is part of the binary compatibility problem I discussed in the first article in the series. It may work if the plugin was built using the same compiler exactly as the application, but it's not a restriction I am willing to force on plugin developers. You can always stoop down to C-style error return codes but that goes against the grain of the C++ plugin framework. One of the main design goals of the plugin framework is to allow both plugin developers and the application developers to program in C++ even if under the covers they communicate in C-style functions across the dynamic library boundary.

So, what's needed is a way to intercept exceptions thrown in the plugin, transmit them across the dynamic library boundary in a safe and compiler-agnostic manner to the application and then throwing the exception again on the application side.

The solution I use is to wrap (on the plugin side) every method in a try-except block. When an exception is thrown on the plugin side I extract some information and report it to the application through a special invokeService() call. On the application side, when the reportError service is invoked I store the error information and when the current plugin object method returns I throw the stored exception.

This delayed serialized exception throwing mechanism is not very conventional, but it achieves the semantics of a regular C++ exception if the plugin method doesn't do anything else after invoking the reportError service.

This section is maybe the most complicated and the most innovative part of the C++ plugin framework. The dual object model is what allows both C and C++ plugins to coexist and be hosted by the same application and also allow the application itself to be totally unaware of the duality and treat all objects as C++ objects. Unfortunately, the generic plugin framework can't do it automatically for you. I present the design patterns and dive into the dual object model of the sample game and you will have to do it for your application object model.

The basic idea of the dual object model is that every object should be usable through the C interfaces and the C++ interfaces of the application. These interfaces should be almost identical other than language differences. The object model for the game includes the objects:

ActorInfo is the simplest because it is just a passive struct that contains information about actor; see Example 3. The same struct exactly is used by the C and C++ and it is fully defined in the c_object_model.h file. The other objects are not so simple.

typedef struct C_ActorInfo_

{

apr_uint32_t id;

apr_byte_t name[MAX_STR];

apr_uint32_t location_x;

apr_uint32_t location_y;

apr_uint32_t health;

apr_uint32_t attack;

apr_uint32_t defense;

apr_uint32_t damage;

apr_uint32_t movement;

} C_ActorInfo;

The ActorInfoContainer is a full-fledged dual C/C++ object; see Listing One.

#ifndef ACTOR_INFO_CONTAINER_H

#define ACTOR_INFO_CONTAINER_H

#include "object_model.h"

#include <vector>

struct ActorInfoContainer :

IActorInfoIterator,

C_ActorInfoIterator

{

static void reset_(C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle handle)

{

ActorInfoContainer * aic = reinterpret_cast<ActorInfoContainer *>(handle);

aic->reset();

}

static C_ActorInfo * next_(C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle handle)

{

ActorInfoContainer * aic = reinterpret_cast<ActorInfoContainer *>(handle);

return aic->next();

}

ActorInfoContainer() : index(0)

{

C_ActorInfoIterator::handle = (C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle)this;

C_ActorInfoIterator::reset = reset_;

C_ActorInfoIterator::next = next_;

}

void reset()

{

index = 0;

}

ActorInfo * next()

{

if (index >= vec.size())

return NULL;

return vec[index++];

}

apr_uint32_t index;

std::vector<ActorInfo *> vec;

};

#endif

I will now dissect it almost line by line so pay attention. Its job is pretty simple. It provides forward-only iteration over a collection (std::vector) of immutable ActorInfo objects. It also allows resetting it's internal pointer to the beginning of the collection, so multiple passes are possible. The interface has a next() method that returns a pointer to the current object (ActorInfo) and advances the internal pointer to the next object or NULL if it has already returned the last object. The first call will return the first object or NULL if the collection empty. The semantics are different than STL iterators where the iterator just advances and you need to explicitly dereference it to get to the underlying object. Also STL iterators can point to value objects and the indicator for end of collection is if the iterator equals to the end() iterator of the collection. There are several reasons I use a different iteration interface than the STL interface. STL iterators support many more styles of iteration with differences nuances than just forward iteration over an immutable collection. As a result, they are more complicated to use and require more code. The main reason however is that the iteration interface of plugin objects should support C interfaces too. Finally, I like the fact that NULL result indicates end of collection and that I don't have to dereference the iterator to get to the object. It lets me write really compact code to iterate over collections.

Back to ActorInfoContainer, it subclasses both IActorInfoIterator and C_ActorInfoIterator and that's what makes it a dual C/C++ object; see Example 4.

struct ActorInfoContainer :

IActorInfoIterator,

C_ActorInfoIterator

{

...

};

It needs to implement both interfaces of course. The C++ interface (see Example 5) is your typical ABC (abstract base class) where all the member functions (next() and reset()) are pure virtual.

struct IActorInfoIterator

{

virtual void reset() = 0;

virtual ActorInfo * next() = 0;

};

The C interface (see Example 6) has an opaque handle, which is just a pointer to a dummy struct that contains a single character and it has two function pointers for next() and release() that accepts as a first argument the handle.

typedef struct C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle_ { char c; } * C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle;

typedef struct C_ActorInfoIterator_

{

void (*reset)(C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle handle);

C_ActorInfo * (*next)(C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle handle);

C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle handle;

} C_ActorInfoIterator;

ActorInfoContainer manages a vector of ActorInfo objects and it implements the C++ IActorInfoIterator interface by keeping an index into its vector of ActorInfo objects; see Example 7. When next() is called it returns the object in the current index in the array or NULL if the index is greater than the vector size. When reset() is called it simply sets the index to 0. The index is initialized to 0, of course.

struct ActorInfoContainer :

IActorInfoIterator,

C_ActorInfoIterator

{

...

ActorInfoContainer() : index(0)

{

...

}

void reset()

{

index = 0;

}

ActorInfo * next()

{

if (index %gt;= vec.size())

return NULL;

return vec[index++];

}

apr_uint32_t index;

std::vector<ActorInfo *> vec;

};

It implements the C interface by populating C_ActorInfoIterator struct. In the constructor it assigns the reset_() and next_() static methods to the reset and next function pointers in the C_ActorInfoIterator base struct. It also assigns the this pointer to the handle; see Example 8.

static void reset_(C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle handle)

{

ActorInfoContainer * aic = reinterpret_cast<ActorInfoContainer *>(handle);

aic->reset();

}

static C_ActorInfo * next_(C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle handle)

{

ActorInfoContainer * aic = reinterpret_cast<ActorInfoContainer *>(handle);

return aic->next();

}

ActorInfoContainer() : index(0)

{

C_ActorInfoIterator::handle = (C_ActorInfoIteratorHandle)this;

C_ActorInfoIterator::reset = reset_;

C_ActorInfoIterator::next = next_;

}

This is the time to unveil the inner workings of the dual object. The actual implementation of each dual object is always in the C++ part of each dual object. The C function pointers always point to static methods of the C++ object that delegate the work to the corresponding methods of the C++ interface. This is the tricky part. Although the C and the C++ interfaces are the "parents" of ActorInfoContainer there is no portable way in C++ to get from one base class to another base class. To do that the static C functions need an access to the ActorInfoContainer instance (the "child"). This is where the handle comes in handy (pun intended). Each static C method casts the handle to ActorInfoContainer pointer (using reinterpret_cast) and calls the corresponding C++ method. The reset() method accepts no arguments and return nothing. The next() method accepts no arguments and returns ActorInfo pointer, which is the same return type for the C and C++ interfaces.

The situation is a little more complicated when it comes to the Turn dual object. This object implements the ITurn C++ interface (see Example 9) and the C_Turn C interface (see Example 10).

struct ITurn

{

virtual ActorInfo * getSelfInfo() = 0;

virtual IActorInfoIterator * getFriends() = 0;

virtual IActorInfoIterator * getFoes() = 0;

virtual void move(apr_uint32_t x, apr_uint32_t y) = 0;

virtual void attack(apr_uint32_t id) = 0;

};

typedef struct C_TurnHandle_ { char c; } * C_TurnHandle;

typedef struct C_Turn_

{

C_ActorInfo * (*getSelfInfo)(C_TurnHandle handle);

C_ActorInfoIterator * (*getFriends)(C_TurnHandle handle);

C_ActorInfoIterator * (*getFoes)(C_TurnHandle handle);

void (*move)(C_TurnHandle handle, apr_uint32_t x, apr_uint32_t y);

void (*attack)(C_TurnHandle handle, apr_uint32_t id);

C_TurnHandle handle;

} C_Turn;

The Turn object follows in the footsteps of ActorInfoContainer and has static C methods that are hooked up to the function pointers of the C_Turn interface in the constructor and delegate the work to the C++ methods. Let's focus on the getFriends() method. This method is supposed to return IActorInfoIterator from the C++ ITurn interface and C_ActorInfoIterator from the C_Turn interface. A different return value type. What a conundrum! The static getFriends_() can't just return the result of calling getFriends(), which is IActorInfoIterator pointer and it can't just do reinterpret_cast or C cast to C_ActorInfoIterator because the offset of the C_Turn base struct is different. The solution is to use a little inside information. The result of ITurn::getFriends() is indeed IActorInfoIterator, but actually it returns ActorInfoContainer dual object, which implements both IActorInfoIterator and C_ActorInfoIterator.

In order to get from IActorInfoIterator to C_ActorInfoIterator, getFriends_() performs up-casting to the ActorInfoContainer dual C/C++ object (using static_cast<ActorInfoContainer>). Once, it has an ActorInfoContainer instance it can serve as C_ActorInfoIterator. It's okay to take a sip of water or something stronger now. You earned it.

The core idea is that the entire object model is implemented in terms of dual C/C++ objects that can be used through either the C or C++ interfaces (with some nudging and casting). It's also okay to use basic types and C structs like ActorInfo that can be used trivially in C and C++. Note that all this mind-boggling stuff is safely entombed inside the application object model implementation. The rest of the application code and the plugin code don't have to deal with multi-language multiple inheritance, nasty casts and switching from one interface to another through the derived class. This design pattern/idiom is admittedly convoluted, but once you the get a grip on it you can see it simply repeats all over the object model.

We are not done yet. I lied. Just two sentences ago I said that this weird dual C/C++ pattern repeats all over the place. Well, almost. When it comes to the IActor (see Example 11) and C_Actor (see Example 12) interfaces this is not the case. These interfaces represent the actual plugin objects that are created using the PF_CreateFunc. There is no dual Actor object that implements both IActor and C_Actor.

struct IActor

{

virtual ~IActor() {}

virtual void getInitialInfo(ActorInfo * info) = 0;

virtual void play(ITurn * turnInfo) = 0;

};

typedef struct C_ActorHandle_ { char c; } * C_ActorHandle;

typedef struct C_Actor_

{

void (*getInitialInfo)(C_ActorHandle handle, C_ActorInfo * info);

void (*play)(C_ActorHandle handle, C_Turn * turn);

C_ActorHandle handle;

} C_Actor;

The objects that implement IActor and C_Actor come from the plugins. They are not part of the application object model. they are users of the application object model. Their interfaces are just defined in the application's object model header files (object_model.h and c_object_model.h). Each plugin object implements either the C++ IActor interface or the C C_Actor interface (and they were registered accordingly with the PluginManager). The PluginManager will adapt C objects that implement the C_Actor interface to IActor-based adapted C++ object and the application will remain ignorant.

In the next installment I will discuss writing plugins. I'll go over the sample application and its plugins. I'll also give a quick tour of source code (there's a lot of it).

This is the fourth article in a series about developing cross-platform plugins in C++. In the previous articles -- Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 -- I examined the difficulties of working with C++ plugins in portable way due to the binary compatibility problem. I then introduced the plugin framework, its design and implementation, explored the life cycel of a plugin, covered cross-platform development and dived into designing object models for use in plugin-based systems (with special emphasis on dual C/C++ objects).

In this installment, I demonstrate how to create hybrid C/C++ plugins where the plugin communicates with the application through a C interface for absolute compatibility, but the developer programs against a C++ interface.

Finally, I introduce the RPG (Role Playing Game) that serves (faithfully) as a sample application that use the plugin framework and hosts plugins. I explain the concept of the game, how and why its interfaces were designed, and finally explore the application object model.

As you recall, the plugin framework supports both C and C++ plugins. C plugins are very portable, but not so easy to work with. The good news for plugin developers is that it is possible to have a C++ programming model with C compatibility. This is going cost you though. The transition from C to C++ and back is not free. Whenever a plugin method is invoked by the application it arrives a C function call through the C interface. An elaborate set of C++ wrapper classes (provided by the application for use by plugin developers) will encapsulate the C plugin, wrap every C argument with non-primitive data type in a correponding C++ type and invoke the C++ method implementation provided by the plugin object. Then the return value (if any) must be converted back from C++ to C and sent through the C interface to the application. This sounds kinda familiar.