A Proposed Invention Cycle

Yesterday, Nilofer Merchant pointed out a great article by the title "Inventing Products is Less Valuable Than Inventing Ideas".

This article mainly elaborates from a paper called "The Second Face of Appropriability: Generative Appropriability and Its Determinants", by Gautam Ahuja (University of Michigan), Curba Morris Lampert (Florida International University) and Elena Novelli (City University London). Appropriability is defined here as "how firms can appropriate value from their inventions" and authors state that "scholars have focused on the idea that inventions create value for firms by being translated into products or by being licensed out" just before they introduce their true scope:

However, from the time of Arrow (1962), and possibly earlier, researchers have recognized that there are usually at least two facets to any invention. On the one hand, an invention is a solution to some technoeconomic problem, a source of enhanced utility or lower cost for some set of beneficiaries; on the other hand, an invention is a concept, an idea that adds to our universe of concepts and ideas and that can itself become a seed for future concepts and ideas. Thus, Arrow’s (1962) abstraction suggests that any invention potentially creates two types of value: an intrinsic value that relates to the problem-solving aspect of the invention and a fecundity, or generative, value that relates to its potential as a springboard for future inventions (Hopenhayn & Mitchell, 1999).

Appropriability hence comes in two flavors: how to capture the greatest share of profits from the problem-solving invention, called Primary Appropriability (PA) and how to capture the greatest share of future inventions that are spawned by this invention and thereby benefit from the new element it has added to the universe of ideas, called Secondary or Generative Appropriability (GA).

The paper mainly focuses on the best strategies for big organizations (firms) to benefit from GA, which, while culturally of interest, is not my primary topic. GA is nevertheless a plainly consistent concept in my favorite topics: lean startups and meshed society.

To invent in a meshed society means understanding what new services are needed by networked individuals. If we agree with Antoine de Saint-Exupery that "illumination is no more than the Spirit’s sudden vision of a road that is long prepared," inventions will probably happen in a meshed society from individuals that can establish a wide social network and gain enough hindsight from these rich interactions. Nilofer Merchant is very talented to describe this ongoing process.

What the text from Ahuja, Lampert and Novelli points out is that neither this invention, nor the service(s) built from it, should be the final goal. Considering that Generative Appropriability is more important than Primary Appropriability, they suggest that invention should be the starting point of a cycle invention – services – invention… Fortunately it is perfectly consistent with the way modern services are built and it is possible to describe this cycle in pretty accurate details.

The Product

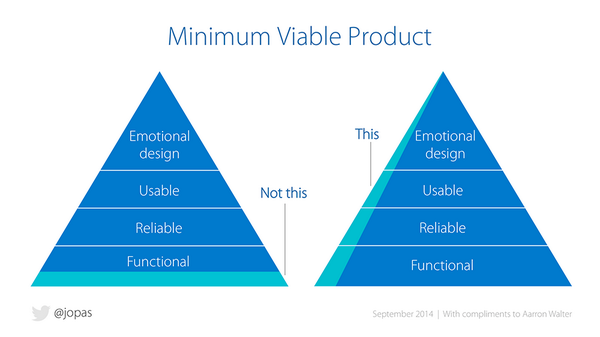

The first step could be called a "rush to the minimum viable product (MVP)". The usual way to do is to pack the very core of the invention into a true usable product. MVP should never mean half-done, but a full designed and functional product that operates only the critical functions (typically five functions). Lean and mean!

Credit Jussi Pasanen (@jopas)

Emergency here comes from a model where things are going so fast on the web that, like when sweating on a running mill, standing still means going backward. Accordingly, being settled on your invention while trying to optimize its Primary Appropriability (for example when writing a business plan to raise lots of money in order to hire a large team to target a fully functional 100+ functions product) means loosing ground and taking high risk that your massive footprint product will not find any place in several years later landscape. My own words, when I estimate that the product comes too late after the invention and we are no longer inventing while not still able to learn from our customers, is "we are starting getting stupid" (typically losing our time implementing functions that people may never use).

Hence the lean startup movement and its foundation principles: deliver early and often (usually thanks to Agile methodologies), engage with your users so you can learn from them (and pivot if necessary), measure success metric so that you can fail fast (so you can succeed faster).

Meshed Society

Great, but these principles are valid in the web as it goes, where kids are taught they can change the world by creating the services they themselves find cool (for example what girls are available on the campus) and pivoting endlessly until they become Facebook. As previously mentioned, in a meshed society, most inventions will be born from the network and, if the lean principles mainly apply, they will fade out in the specific way a meshed society operates; instead of "gaining users and engaging them", inventors will seamlessly offer the societal network a new service. To "make a dent in the world", as Nilofer Merchant usually phrases it, will no longer mean creating a mogul company to "rule them all" but truly raising the meshed society one step further.

To get the point here demands a little more accuracy about what meshed society actually means. To make it short, there is growing evidence that we already entered the post-industrial era and that the very root our societies are built from must be questioned.

From early times in human life, we inherited the hierarchy, as many other animal species did. Hierarchy for human has been meritocratic (the Dominant Male), then hereditary (some got stuck there) or elective. Jeremy Rifkin, in The Third Industrial Revolution explains that the pyramidal hierarchy became the way to go in the industry during the first Industrial Revolution when railways giants became the first private organizations to need thousands of employees to operate. For centuries, it has been delusive (or poetic) to imagine other ways to organize.

The web as we know it is probably a vector of change that only compares in history to the invention of the printing press… but it compares with the printing press "power thousand" since it is not just a communication system, but an operating system, a place where information can not only get published, but also processed.

We all know the recent history of the web, from a place where official and institutional information was available to the place where people co-create – the famous Web 2.0 coined by Tim O’Reilly. Many have tried to imagine the next web – due to a complete lack of creativity they usually called it Web 3.0. Web 3.0 would either be a semantic web or the web of objects (WoO) or web of things (WoT); they forgot that, as quoted by Jean Bodin, "there is no wealth nor strength except in men" and the next web can’t be anything but the operating system of a new kind of democracy. What is to come is not a technical Web 3.0 but a humanistic Meshed Society; a worldwide bionic neural network born from the ability to build knowledge from shared information.

When discussing Generative Appropriability (GA) versus Primary Appropriability (PA), it is of great interest to compare Xerox with Apple, stating, as Ahuja et al. did, that the former "has created many inventions but has not necessarily been successful in building on many of them" while the later "is an example of a firm that has managed to be creative in both building on its own inventions (e.g., the iPhone and iPad based on the iPod) and in precluding (or at least delaying) other companies from successfully building on its ideas." It is probably of utmost interest to foresee how it can get transcribed in the meshed society core concepts, in the wisdom of crowds.

The cycle

Let’s go back to the invention – product – invention cycle.

We know that inventions will happen from using the network to be able to "rise above to crowd" and gain the proper hindsight. We also suggested that a minimum viable product should quickly follow the invention in order to reward the network with a new service. Then ideally iterate, somewhat like a respiration process. But this mechanism is not generative by itself! On the contrary, the aim of the MVP in the lean startup theory is to build a light object in order to make it easier to find the place where it can fit in the current universe of services, then to iterate to grow step by step, and eventually pivot when there is no place left for a larger object in the previously targeted direction. If the product can seamlessly follow the invention, it is not natural at all to have a new invention be born from it.

It follows that our cycle will hardly be a two stroke engine! But after all, the most famous continual improvement cycle, the Deming Wheel is a four stroke engine, and we can probably mix its Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) iteration steps with the lean startup concepts. Since our core principles are that, in a meshed society, invention will come from engaging with the network then (remembering Saint-Exupery’s quote) have illumination emerge from processing the flow of interactions using a synthesis oriented reactor (say a creative human brain), we can now name the missing strokes and end up proposing an Engage-Process-Invent-Build cycle.

To be continued… after some more interactions. Please let me know your opinion.

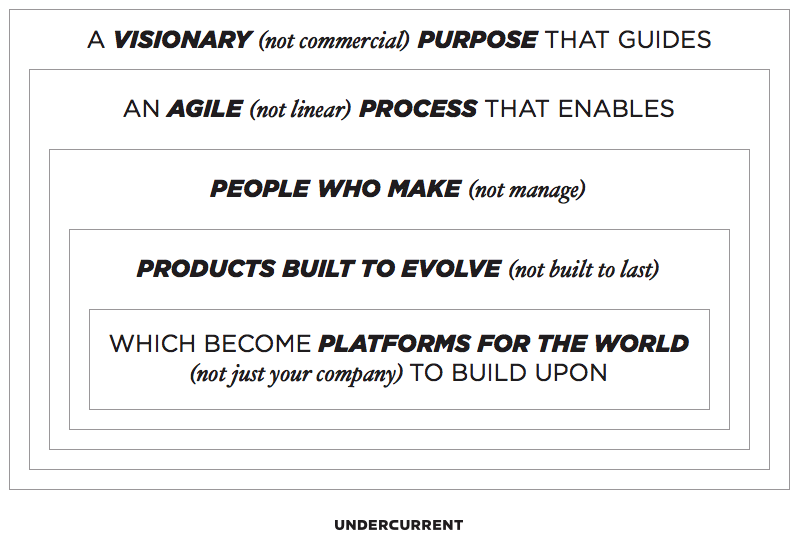

Added (on November 12), this drawing from a previous post (Responsive Organizations) that pretty well fits in the landscape, even if not explicitly cyclic (it is indeed!).